Birds are the migrants that need our help.

Birds are the jewels of our global wildlife,they bring colour, sound and movement to our lives and need our protection in a world where we have depleted their environment.

Evolution has driven birds to migrate, in this sense they are migrants.

Of the many families of birds, shorebirds are perhaps the least known. This is because they generally spend their lives in remote areas, away from people. Their home, in the summer where they breed and where they spend the winter are usually different. Often thousands of miles apart and their innate need to travel between the two is their migration.

Enabling the birds to fly these enormous distances, between the breeding grounds and the wintering grounds are a series of important refueling stops.

These refueling stops are like oasis’s in an otherwise inhospitable desert. Take away these oasis’s and the birds will die.

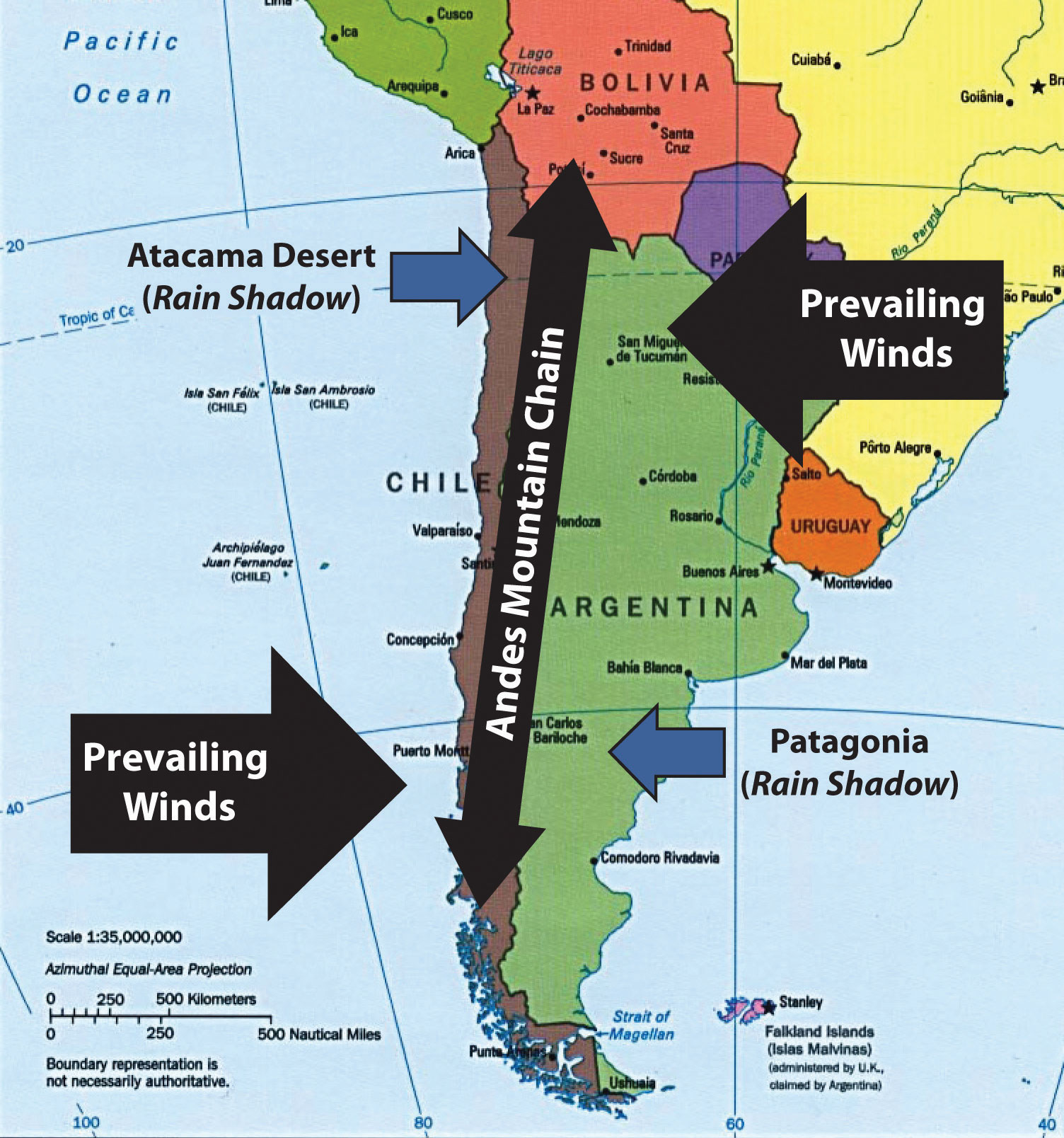

In South America there are about 12 families of shorebirds. This designation of birds is based on evolutionary and biological criteria and is highly scientific.

Another simpler way to group the species of shorebirds would be, as to how they migrate.

For instance the Andean Avocet moves very little. From lakes on the higher reaches of the Andes where they breed, down several thousand feet to the lower and less harsh slopes for the winter.

In this same category would be the Two-banded Plover. Like the Andean Avocet they live only in South America and migrate short distances, more a seasonal movement than a long-distance migration.

Two-banded Plover map; breeding in southern Patagonia and wintering some short distance to the north

Another category of shorebirds would be those that do not breed in South America. Instead they breed in North America and fly to South America for the winter. This gives them year round access to food.

Birds in this category would include Sandpipers, the Red Knot and Wilson’s Phalarope and many other species.

Wilson’s Phalaropes breed in the northwest of North America, on small lakes set in the Great plains amidst the Rocky Mountains. In late summer they need to leave, as the winters are cold and the lakes freeze over.

They fly south, heading for South America. En route they stop off at saline lakes. Lakes such as Great Salt Lake in Utah, Lake Abert in Oregon, Goose Lake on the Oregon-California border, and the Lahontan Valley lakes in Nevada. At these places they rest and feed for a few days. This enables them to store fat reserves in their muscles, the necessary fuel to continue their journey southwards, to Argentina and Chile for the winter.

Wintering sites (refueling stops) such Los Pozuelos, San Antonio Oueste and Mar Chaquita, all in Argentina, are vital for these species.

Birds are the migrants that need our help and everyone can do a little to help. Helping can be as simple as joining the local or national conservation organisation. If you do not know if your country has one, look at Birdlife International