Photo Blog

It was a crazy trip, going up to nearly 4600m high and we weren’t sure which of us was the dafter, us for being there or the Coots that lived there.

Paula and I took a ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition to Laguna Blanca and the surrounding altiplano, situated in the high Andes of Catamarca, Argentina.

We were searching for three species of Coots, the Giant Coot, the Andean Coot and the Horned Coot.

Many birdwatching groups visit Argentina, only a few manage to get to the Altiplano, but the wildlife on these dizzyingly high plains is quite special.

The image below is of a Giant Coot.

All three of these birds look very similar at a distance, however a closer view of their heads show quite different frontal shields. The frontal shield consists of a hard or fleshy plate of specialised skin extending from the base of the upper bill and over the forehead. Each species has its shield coloured and shaped differently. The function of the shield is closely tied to sexual attraction, display and territoriality. As with so many bird families in the Andes,these three species occur at different altitudes, though there is some overlap in distribution. All together the South American genus of Coots demonstrates beautifully the concept of allopatric speciation.

This Andean Coot has a large bulbous red knob on its forehead.

On we travelled through the Puna, Cardon Cactus either side of us, Andean Swifts scything across the sky as we drove up and up.

Eventually at Laguna Blanca we found the largest of the coot family the Giant Coot, together with James’s or Puna Flamingo.

The Giant coot weighs over 2 kilos and is considered flightless. Not surprising it builds an even bigger nest made up of stack upon stack of aquatic weed.

We had to travel quite a bit further on before we discovered the other Coot we were searching for, the much rarer Horned Coot.

Eventually we found ourselves in a barren, stark, toffee and turquoise coloured landscape, where the air was so thin I had to take Oxygen.

The Horned Coot is only found at a altitude in excess of 4500m and we had discovered several birds on a diamond shaped lake.

Horned Coots are rare and it was not so long ago that they were hunted for food.

Light headedness is a sign of oxygen depletion but it could have been excitement in watching this rare coot.

We would have been as daft as a coot to stay any longer so reluctantly returned to a lower altitude and a cup of warming soup in a small hostal.

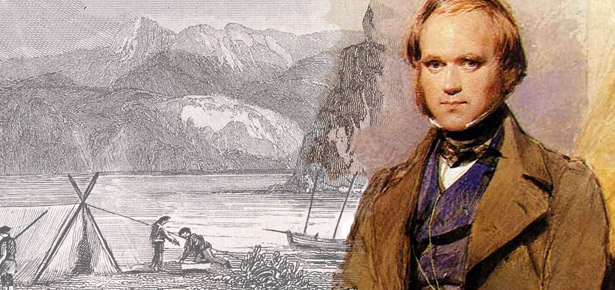

Without being rude, this is all about Charles Darwin’s Rhea.

For those who think I have made a spelling mistake or know little about birds, Charles Darwin’s Rhea is a bird.

When Charles Darwin was on the Beagle, voyaging around South America, they laid anchor in Patagonia. There, the expeditions artist shot what he thought was an Ostrich. Before Darwin had thoroughly studied it, the poor bird had been skinned and cooked for the crew to eat. Only then did Charles Darwin examine the bird and discovered it to be new to science. The bones from this bird and a few of the remaining feathers are now held as the ‘type specimen’ for the species known as Darwin’s Rhea.

Darwin’s Rhea, also known as the Lesser Rhea, is a large flightless bird and is the smaller of the two species of rheas in South America. It is found on the Altiplano and in Patagonia but is generally uncommon.

Paula and I spent many hours scanning suitable habitat trying to see this bird and although it’s a meter and a half high, it is beautifully camouflaged and because it has been mercilessly hunted is wary of people and keeps to thick scrub.

We camped for a week on the Valdes peninsula on the Atlantic coast of Argentina. There is only one place where you can camp, this is in the small town of Puerto Piramides. As part of our ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition we were there to photography Killer Whales and birdwatch but did not expect to see Darwin’s Rhea, but we did and were thrilled.

Darwin’s Rhea with its feathers fluffed up, ready for display.

Rheas have feathers but as the birds lost the power of flight, perhaps hundreds of thousands of years ago, the feathers have become more decorative. They do not have the special barbules that connect each one tightly together, as in all other birds. The ‘comb like’ vestigial feathers across the Rhea’s back are long, golden edged and white tipped. These delicate fans were used to adorn women’s hats a century ago, to make them look beautiful. For the Rhea this untidy mass of plumes have a dishevelled look, but their use comes in the courtship display. At that time the Darwin’s Rhea prances and pirouettes on the Patagonian steppe, flaying his useless wings around like a dervish, with electrifying and magnetic effect.

It is common for one of the adults to look after not only their brood of chicks but also those of another pair. On one occasion we saw an adult with a group of fourteen chicks.

This little animal could have been a film star.

In the new film ‘The Lone Ranger’, the hero is copying a classic animal strategy at avoiding predation, having an eye-mask. Even Johnny Depp has disruptive facial marks.

The Lone Ranger and his sidekick Tonto were among my favourite childhood heroes. What I remember most was the mystery of the Lone Ranger’s eye-mask. I couldn’t understand why he wanted to hide his true identity, after all they were the goodies.

Later I realised that they wanted to hide from the baddies, faces are bright and easily seen, the Lone Ranger needed to camouflage himself.

In Argentina, the ‘Living Wild in South America’ team of Paula and I went looking for a special animal we had heard of but never seen, the Plains Vizcacha. One of South America’s wildlife specialities.

The Plains Vizcacha was once abundant in the Pampas grasslands of central Argentina, but not now.

Intensive agriculture has transformed the Pampas. The burrowing habits of the Plains Vizcacha became a nuisance and it had to be eradicated.

We found them in an area of semi-woodland, close to grassland, living in burrows. They are crepuscular, only emerging at dusk and dawn, and their Lone Ranger eye-masks help to camouflage them.

Hey ho Silver!

Long before the Spanish colonised South America there was a rich and diverse indigenous population, hundreds of ethnic groups, each with their own language and culture. The visible signs of these cultures and the artifacts they left behind can be referred to as Pre-Columbian art.

Whilst walking the hills and mountains of Argentina, on a really lucky day, we sometimes come across places such as this lovely valley nestled close to the Bolivian border. In this valley we found a huge boulder, on one side of which were etched Petroglyphs or rock carvings.

Even luckier still we sometimes find people who show us artifacts they have found.

Like this beautifully crafted head of a mace.

Or this stone axe head, both of which are deadly weapons and would have taken many weeks of hard painstaking work to make.

We like to imagine that somewhere in this green and fertile valley there is a cave where all those thousands of years ago, people lived.

They would have hunted, slept, eaten, loved each other and spent time making these tools as well as painting sacred rocks with images that were important for them.

They really did live Wild in South America, we are just travellers passing through.

The strongest animal in the World is the one that can carry the most weight. It’s an insect and a special sort of insect, a beetle.

This is a Rhinoceros beetle and it uses its massive horns to fight with other males to secure dominance and attract female beetles. They will also use their horns to dig their way to safety, under small rocks and logs during the day. It has been shown that an adult Rhinoceros beetle can carry 850 times its own weight on its back. There are several different species of Rhinoceros beetles, all live in South America and they all have similar lifting capabilities.

When the ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition reached Peru we stayed at the Villa Carmen Biological research station close to the Amazon basin. In the evenings we saw a number of these 100 mm insects careering through the forest. Like little helicopters, they manoeuvred through the dense trees and occasionally fell to the ground near a light. We picked this one up and spent an hour or so photographing it. Even having the beetle in our possession it was not easy to take a good wildlife photograph of it. There will be a whole new blog dedicated to this!

Beetles like this are common in South America and were one of the wildlife highlights we wanted to see. We wanted to see the strongest animal in the World.

This mahout rides on the back of his elephant in Madyha Pradesh, India. This Indian Elephant couldn’t carry much more weight than this, in fact only 25% of its own weight, a puny amount compared to a Rhinoceros beetle.

Bar a feather or two, the biggest flying bird in the world is the Andean Condor, an iconic part of South America’s wildlife.

The Andean Condor is also one of the world’s longest lived birds. It can fly higher than any other bird and it’s one of the few birds revered in mythology and common culture.

It can live for about 50 years and does not become sexually mature until about ten years old.

Its mating display is an exaggerated series of outstretched wings and bows, accompanied by a clicking sound whilst the bare facial skin of the male turns bright yellow.

Once a pair bond is established they stay together for life.

The female lays only one egg every two years, this takes nearly two months to hatch.

The youngster cannot fly for 6 months and is partially dependent on its parents for two years.

They do not build a nest, instead, securing their egg among boulders or inside a small cave. Roosting at night is always on a ledge set in sheer rock race, from such places they can easily land and take off.

When Paula and I of ‘Living Wild in South America’ were journeying in the very north of Argentina we stayed a few nights by the village school of Yavi Chico, right by the Bolivian border. Close to the school was an impressive escarpment, clearly visible from the school playground and most of the classrooms. We watched the escarpment carefully and found that up to fifty Condors would roost for the night on its narrow ledges. No one in the school knew this and most of the teachers admitted they had never even seen a Condor, so our binoculars were in full use for a few days.

The Condor is so much bigger that other Vultures. Look at the difference between an adult Condor and a Black Vulture.

If you are birdwatching in South America, Condors can be seen almost anywhere in the Andes. Walking the remote trails one has to be lucky to see them on a kill or close to. In Peru the Colca Canyon provides a rare opportunity to see them at eye level.

In the Mendoza province of Argentina there is also a good watch point in the hills above the town of Olta. Go into the town and ask for directions, it takes about an hour to drive there, drive as far as you can and the road stops by a tiny farm. Javier, a friendly local guide, took us to the viewpoints.

The use of Seaweed to cure a wide variety of cancers is well documented.

Brown seaweed and a variety of kelps are the best, but where does this seaweed come from?

The best seaweeds come from the Pacific Ocean gathered by communities of poor people living on the coast of Chile.

Paula and I had heard of these communities and took the ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition off to Chile to find out what was going on.

As we travelled up the Chilean coast we came across families living in makeshift shacks right on the beach-line and their living was made by collecting seaweed.

We chatted to many of the seaweed gatherers and they were generally content with their work. With so few other employment opportunities, seaweed gathering enabled them to live in their communities, close to the beautiful Pacific Ocean, supplementing their income with artisan fishing.

Men and women, mostly middle aged or older, would be out collecting at dawn. Many of them knew that seaweed cures cancer and that was one of their reasons for collecting it.

Many went deep into the sea, swimming between rocks and pulling the weed out of crevices, the surf sometimes crashing over them.

Some were diving deeper underwater to obtain different and more valuable types of seaweed.

The seaweeds would be left in the sun to dry and then collected up. It was back-breaking work.

Once a week a truck would pull into the village and the seaweed was piled on top. This oceanic treasure was then driven up the coast to a port for eventual shipping to Japan.

This bird has a bill as bent as a crooked lawyer!

In reality the bent bill enables it to swish back and forth in shallow alkaline lakes for fly larvae.

The bird’s name is the Andean Avocet and it is not easy to find. Birdwatching is impotrant to the local economy and birdwatchers travel from far and wide to search for this uncommon wader but because it lives above 3,500m in elevation, along the high Andes of Peru, Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina many birdwatchers are disappointed.

Our ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition to Los Pozuelos National Park in the very far north of Argentina was fortunate, as we found groups of the birds feeding amongst Wilsons Phalarope and Andean Flamingos. Los Pozuelos is a Ramsar site and an excellent place for birding travellers to visit.

This bird with a bent bill is really a beauty. Its striking black and white plumage is a stark contrast to the muted shades of the Puna.

If you want to do successful macro photography in the wild, think about having a field studio.

Paula and I were in the depths of the amazonian rain forest in Peru, when we found a Rhinoceros beetle near to our camp. The Rhinoceros beetle is an iconic tropical insect, a celebrity.

Celebrities need attention and we wanted to give as much of our photographic attention to this beetle as a wildlife photographer in East Africa would do for the impressive mammal after which it is named.

The difference with an insect this size, is that to a great extent you can contrive almost all the factors that might lead to achieving a great photograph.

The first thing we did was to carefully place the insect in a cool place, a fridge. This does the insect no harm at all, the insect relaxes and slows down.

We then prepared a place for the photographic session.

We wanted to have a photograph of the beetle in its natural rain forest habitat and it took us about an hour to find a suitable location. There, we built a little ‘stage’, celebrities like stages on which to strut. We used strong boxes, camouflaged mats as well as lots of natural material.

Paula and I have been in South America for over a year now, photographing and filming the wildlife. Our expedition into Peru was part of our ‘Living Wild in South America’ series, so we carry a lot of this equipment with us as routine.

We made the stage as natural looking as possible and then brought in the equipment. An Elinchrom Ranger ‘quadra’ system, comprising two lights and a Canon D6 camera on a gitzo tripod.

We took a series of test shots using a stone, moving it in various positions, looking at our results and tweeking the camera settings until we were happy.

We wanted a variety of shots, so we used two lenses the Canon 180mm macro lens which I have had for six years and love, love, love, and a new Canon 8-15mm fish eye, which I have not used much, finding that it requires very special circumstances in which it is useful, perhaps this was to be one of those situations?

Then we introduced the beetle. At first it did not move. Minutes and minutes passed by. We could not take any images as the insects legs were tucked under its body giving it an unnatural appearance. We waited, ten minutes went by, we were getting apprehensive, then suddenly a movement, up came the legs and slowly the beetle started to move.

The first few seconds are vital, this is the best time for that great image. The camera shutter snaps, snaps and snaps again, there is no time to check the settings or position, the pre-planning is now paying off.

This was my favorite picture, the celebrity on her stage and in a perfect setting.

At over 30 degrees the insect became fully mobile and tricky to deal with so the kindest and most responsible thing was to take this denizen of the forest back to where we found it.

You do not need this amount of equipment, simple flash guns can be sufficient, especially used with reflectors. But we like the flexibility of the ‘quadra’ system and have used it for many types of ‘field’ situations.

If you are interested in macro photography we would recommend you to look at Alex Hydes’ work, his is some of the very best macro photography.

The official flower of friendship is the Alstroemeria.

Resembling a miniature lily, alstroemeria, often called the Peruvian Lily or Lily of the Incas, was named by Carl Linnaeus after a friend of his, Baron Claus von Alstromer, a Swedish baron who collected the seeds on a trip to Spain in 1753, the seeds having been brought back by an unknown mariner.

The ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition came across this flower in the wooded valleys of the Laguna Torca National Park, Chile.

It was Christmas Eve and Paula and I had been up since dawn, by the Laguna, photographing birds. This National park is good for Bird Photography, birdwatching, nature and wildlife in general. There is easy access to the lagoon, with a board walk through the marsh. We saw a diverse number of birds, including Black Swan and the uncommon Snowy-crowned Tern. During the middle part of the day we needed somewhere cool to walk and the woods were ideal and this is where we found the lovely Alstroemerias in flower.

Symbolizing friendship and devotion, the alstroemerias’ leaves grow upside down, with the leaf twisting as it grows out from the stem, so that the bottom is facing upwards – much like the twists, turns and growth of our friendships

The National Park has a good campsite with toilets and washing facilities. It is also only a mile or so to the Pacific coast and there are plenty of small shops in the nearby village of Llico.

A species of Chilean Palm tree has been almost exterminated in the wild by the rapacious destruction of the native woodlands for a super sticky and very tasty treacle.

Fortunately the National Parks authorities in Chile CONAF, have a programme to grow young seedlings and transplant them.

Paula and I whilst on an photography expedition for ‘Living Wild in South America’ found a small nursery of the Palms (Jubaea Chilensis) in the grounds of the Laguna Torca National Park in Central Chile.

We were attracted to the flowering spike of one of the Palms as there was a Shiny Cowbird taking nectar from the florets. Each time the bird dipped its head into the flower head, pollen was deposited on its head. We saw the bird go to several flowers and thus the bird was acting as a pollinator.

The Chilean Wine Palm is so named because a strong beverage like treacle can be made from the sap from its trunk, unfortunately to do that one has to cut down the tree. This photograph was taken in one of only two locations where the Chilean Palm grows in the wild, the La Campana National park in the Andean foothills, N.W of Santiago.

Charles Darwin climbed to the top of Cerro La Campana (1828 m) on July 16th 1834, I quote from his writings ” These palms are, for their family, ugly trees. Their stem is very large, and of a curious form, being thicker in the middle, than at the base or top. They are excessively numerous in some parts of Chile, and valuable on account of a sort of treacle made from their sap. Every year in the early spring, in August, very many are cut down, and when the truck is lying on the ground, the crown of leaves on the top is cut off. The sap then immediately starts to flow from the upper end and continues to do so for many months. The sap is concentrated by boiling , and is called treacle, which it very much resembles the taste”

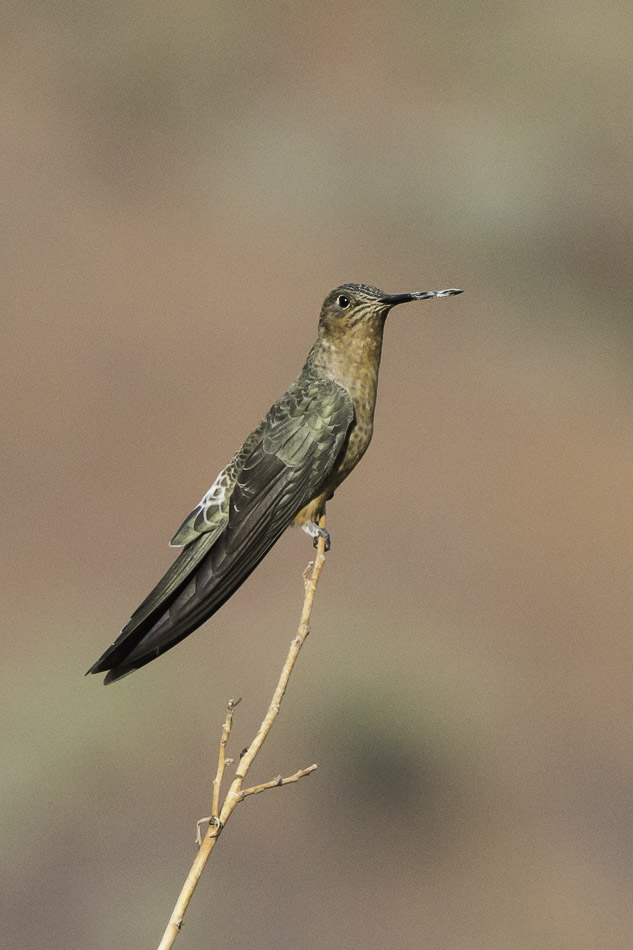

Since Darwin’s time the area has been a magnet for nature, wildlife lovers and birdwatchers and the national Park is one of the most visited in Chile. It was declared a National Park in 1967 and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1985 and is a wonderful location to see the Giant Hummingbird.

The Giant Hummingbird i s also known to pollinate the Chilean Palm.

Of the three species of Flamingo in South America, the one with the distinctive red “knee-caps” is the Chilean Flamingo.

It feeds by shuffling its feet in the water, this stirs up the sediment and brings into suspension lots of juicy “flamingo fare” algae and crustaceans.

This activity attracts other birds, such as the Wilson’s Phalarope to take advantage, one bird indirectly helping another, helping friends feed.

This unusual bird behaviour was recorded by the ‘Living Wild in South America’ team at the Salar De Atacama lagoons in Chile.

Sooty Shearwaters are one of the most numerous seabirds of the Southern Oceans and breed in Southern South America.

Paula and I were based in the village of Boyeruca on the coast of Chile. As part of our ‘greatest birdwatching adventure in the world’ we spent a few days counting the Sooty Shearwaters and one day in December we counted tens of thousands moving south.

Sea watching for birds is one of the more difficult aspects of birdwatching. Many times we have sat on the dunes of Spurn Point in England as an easterly wind blew in our faces. Shapes over the waves indicated possible species of Skua and concentration and perseverance is needed to secure a satisfactory identification.

Generally sea watching off the central and northern coast of Chile is a more pleasant experience. Off shore there lies the Humboldt current and this brings in its wake a plethora of wildlife, such as fish, birds and mammals. It’s warm, sometimes hot, and the birds are much more numerous.

The birds that December day, were no ‘will o’-the-wisps’ over the waves. Instead black squadrons swarmed over the sea, wheeling as Shearwaters do, driven upwards by the crest of each wave and then downwards by the wind, a tumbling tumult of birds.

Mixed in with the ‘Sootys’ were also Pink-footed Shearwaters and various species of Petrel.

Considering that these birds are global in their distribution, it is a sobering truth to realise that they and many other seabirds are declining, with over-fishing as their main threat.

International agreements on fishing quotas and net size will all secure seabird conservation.

.jpg)

Breathtaking scenery in an environment where even taking a breath is difficult, this is the nature of bird watching in the high Andes.

Of the many habitats to be found in the Andes, the one Paula and I have loved finding the most, has been the marshes in the otherwise arid and stony landscape.

These are called Bofedales and are very special.

They are formed either by water flowing directly into them from glaciers high among the mountain peaks or from underground water that oozes to the surface. They can be a marsh, a bog, a wetland, even highland pools, but to Andean people in Argentina, Chile, Peru and Bolivia they are Bofedales and are a valuable resource for both man, his livestock and wildlife.

We came across this Bofedal after crossing the arid plains of the Nevado de Tres Cruces National Park in Chile. Its verdant mirage attracted us from afar. At last we looked upon its circular grassy knolls, clouds floating across the shimmering reflections and were entranced.

We stayed a few days, isolated but not lonely. Guanacos came down to drink and a dozen species of birds as well. Invisible to their mountain eyes, we sat in a hide and watched their comings and goings, as a seemingly deserted landscape gave up its creatures to the life giving oasis in front of us, the birds of the High Andes.

A Black-fronted Ground-Tyrant. We saw up to six individual birds in the area.

This pair of Puna Teal visited us every morning.

Small groups of Greenish-Yellow Finches were always down at the water’s edge.

For our ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition to this area, a 4 x 4 vehicle is necessary and our Toyota Hilux was admirably suited. An expedition like ours is well equipped, we carry oxygen and have sufficient water and food for at least a week. Birding in the Andes is difficult enough but when searching for birds of the High Andes, we try to minimise risks.

The Elfin woods of South America are now hidden away in the highest most inaccessible parts of the great Andes mountains, having retreated there to escape the axe.

Survival in the high Andes is tough. It is said that there are only two seasons, the fierce heat of the day and the numbing cold of night time, both seasons interrupted by storms and gales.

The one tree thriving in this mean climate is the elf sized Polylepis tree, a type of rose. Contorted boughs and twigs show its constant fight with the wind. The trees thick red surface, made of layers and layers of insulating bark point to its nightly struggle against the cold.

If nature wasn’t enough of a force to fight, there was man, who had the same enemies as the tree. But man could fell the tree in the knowledge its wood would keep him warm. So it was for century after century until the the tiny trees were nearly gone.

We set out on a ” Living Wild in South America”, expedition, to find some of these elfin trees and like most pixies they evaded us for months.

Eventually we found a small copse near Santa Catalina, the border country between Argentina and Bolivia. Here, tucked away down the steep slopes of a gully, we could see the evergreen mantle they cast over a stream. It took an hour of tricky, slippy, sliding steps to stand in their shadow.

At a distance they reminded me of another sacred tree, the Yew. But these trees were small and grew amid succulent cacti.

Never have I seen such a jumble of trees. Nothing was straight, everything about their trunks, boughs and branches was twisted, warped and wrenched. In their bark you could see contorted faces, beasts and long noses, limbs reaching out as if to grab you. These were trees crafted to sustain the elements.

In this arboreal grotto I heard long exaggerated notes of a bird. Some way off on tangle of twigs like the end of a witch’s broom, a pair of Streak-fronted Thornbirds perched and sang their duet. This was a living vibrant woodland after all, and not just for Elf trees.

Boiling pools of water,gassy fumaroles, mud volcanoes, sulfurous fumes, bubbles and spouts, jets of steam, all these and more, are to be found in a land of Geysers.

Ten million years or more ago the South American continent gradually collided with the Nazca plate. Over expanses of time beyond mans ability to comprehend, this collision led to many great events. The Andes reared upwards into the sky and deep deep in the depths of the earth, the red hot inner core was ruptured, forcing incandescent heat to the earths surface. Volcanoes were formed from Tierra de Fuego (the land of fire) to the Caribbean. The surface of South America was crafted in a cauldron.

There are a many places along this ring of fire where small amounts of heat causes geysers and pools of steaming water.

The geysers are highly photographic, but to see them at their best one needs to be present at dawn.

One of the most popular areas to find geysers is close to San Pedro de Atacama in Chile the El Taito geysers. From this town it is about a two hour drive to the geysers. Visitors have to leave at 4.00 am to catch the geysers at their best.

Paula and I are fortunate as we have our own vehicle, which we use for our ‘Living Wild in South America’ expeditions. We were able to drive up the day before, and sleep overnight, this meant we did not have to get up at a silly hour. Though camping at 4000 m is no fun either, headaches, shortage of breath and cold being just a few of the disadvantages.

If you do have the opportunity to go, make sure that you take breakfast with you. No food or drink is available on site, and its very cold, when you are not close to the Geysers.

When the Condor returns to an area from which it has long been absent it is good for the biodiversity of that area. It is also good for the people who live there because, for some, the Condor is sacred.

l

l

Ancient peoples and especially the Incas, believed that the Condor was the spirit messenger of the sun. It was this huge bird which took the souls of their dead to heaven.

Only a bird as large and powerful as the Condor could master the awe inspiring landscapes of South America with the towering peaks of the Andes, endless deserts and luxurious forests. To the indigenous peoples this bird was regal and needed to be treated as such.

More recent times have seen these traditions and sympathies long disappear. With the introduction of goats and sheep, extensive livestock rearing became the mainstay for making a livelihood on the windswept hills. Now the Condor was seen as a threat and was hunted mercilessly, poisoned and shot.

Over much of its historic range the Condor followed the same fate as the indigenous tribes, one of almost extinction.

The twentieth century conservation movement was a last ditch turning point for the Condor and a breeding and release programme, PCCA, was started at Buenos Aires Zoo. The principal characteristic of this programme was simple, it was to have two elements, two wings like the bird. One wing was to be scientific, a breeding programme based around sound biology. The other wing was to be cultural, incorporating the traditions and beliefs of the ancient peoples.

Condors reproduce very slowly. They do not breed until they are ten years old and then only one egg every two years. They mate for life and if their mate is killed, the other partner does not pair up again. Scientists located breeding pairs, located nests and as soon as an egg was laid, they removed it to Buenos Aires for artificial incubation. The Adult seeing the original egg gone, promptly lays another, and the parent birds are then left in peace. A chick takes two years before it is able to fly and during that time PCCA staff feed the Condor chicks by using a ‘Condor looking puppet’.

Paula and I on our second ‘Living Wild in South America’ expedition joined the Condor re-introduction team in Patagonia and experienced a Liberation ceremony first hand.

This is the release site for the two year old chicks, a remote and secure location deep in the middle of Patagonia, a habitat perfect for the great birds and easy flying distance to the Andes.

The day of the release is eagerly anticipated by the local communities. Hundreds of people are involved with schoolchildren arriving on coaches from near and far.

Each bird is tagged with identification markers and satellite transmitters.

Wise men, elders of the indigenous community lead the Condor release. For them this is an important day, a sacred day, their spirit bird is about to take to the air and fly for the very first time.

People bring forth personal items of significance, Condor feathers they have found, hand made fabrics dyed with natural colours from the bush, peace pipes, amulets and talismans.

Prayers are chanted, invoking the mountain winds to to take care of the birds, for the birds to find food and for a long life to be lived.

The birds are released and people are amazed as they look upon the largest flying bird. The Condor returns to their community.

Children cheer and hold aloft their own feathers.

The birds rise into the air, circle above the people below and drift towards the mountains.

Leaving people with their own thoughts, about the spirit messenger of the sun.

Also perhaps, about the insignificance of mankind in such a landscape of snow capped mountains and endless Patagonian plains, a landscape where only the Condor reigns supreme.

There have always been migrants. People become migrants for safety, food and shelter. That’s all most animals want too.

It’s dangerous to leave your home and travel, people do not leave their homes without good cause.

It’s the same for animals.

Animal migration can take many forms. Some birds, like this Andean Flicker which is a type of woodpecker, migrate up to the high sierras of the Andes in South America, the Puna, to nest during the summer. The harsh winters provide little food for the flickers and so they move lower, perhaps thousands of meters, where the environment is kinder.

Likewise for Andean Geese, they nest even higher, on the Altiplano at a dizzying 5000 meters. When the autumn winds start to blow they fly lower, to warmth and green pastures.

Humans are often unaware of the great bird migrations that seasonally criss-cross the skies. The same thing happens with human migration. Few see it and fewer experience it.

For birds and other animals one thing is assured: those migrants that do arrive at their new homes are able to feed and rest unmolested.

This is not the case for most human migrants.

I love red, but then I’m a Leo!

Red is often associated with strong negative emotions, to signify violent conflict. “Red in tooth and claw” says Tennyson, in an attempt to draw attention to the callousness of nature. I prefer another use of the phrase, by Richard Dawkins, who uses it to better understand the relentless struggle between species, or the ‘survival of the fittest’.

There is no colour that is more positive, draws more attention or stands out more than red. I love red and I like photographing red things and there are plenty of red animals to photograph in South America.

This is a Vermilion Flycatcher, it’s the most outlandishly red bird I know. It is ridiculously red and it almost hurts to look at it. Why it is red I do not know. What advantage can such a gaudy colour be? We have seen them quite commonly as we travel through South America on our ‘Living Wild in South America’ wildlife photography expeditions.

Vermillion Flycatchers are much sought after for captivity, but once in a cage they lose their brightness and sparkle.

In the darkness of a tropical forest, being green or brown may help you to hide. But to attract a mate the average animal needs to do something brash, something to get noticed and butterflies are very good at doing just that.

This is a type of Heliconius butterfly that we saw in the Alisos National Park, Argentina.

A flash of the wings and this forest butterfly will definitely get noticed and not only by the opposite sex of the same species. It could be noticed by a predator and then red means caution. Many butterflies will eat toxic plants that make them taste bad. So if you know you taste bad you can make the most of it and flaunt yourself.

So RED can mean ‘HERE I AM, COME, I LOVE YOU’ or “STOP, GO AWAY, I TASTE BAD”

Whilst we were camping on the north coast of Chile we were able to photograph some bright red and quite toxic, Sea Anemones. Whilst we were doing so we noticed that small prawns were using the anemones as hiding places. They clearly were not harmed by the long antennae.

The ‘Latin’ nature of Argentinians is often epitomized by either the slinky, sexy Tango dance

or the wild exuberant Gaucho.

These passionate people are proud, love life and like to be noticed, much like the Vermilion Flycatcher or Heliconius butterfly.

I love red.